Juxtaposed with the nearby bustling commercial centers on SE Hawthorne Blvd and Division Street, Portland’s Brentwood-Darlington neighborhood feels quiet and residential, even suburban.

Residents south of Foster Road between SE Cesar Chavez Boulevard and SE 92nd Avenue have enjoyed relatively low housing prices compared to parts of Portland closer to the city center. But the neighborhood quaintness and single-family housing affordability have come at the expense of other important amenities, like transportation infrastructure and convenient, accessible grocery stores.

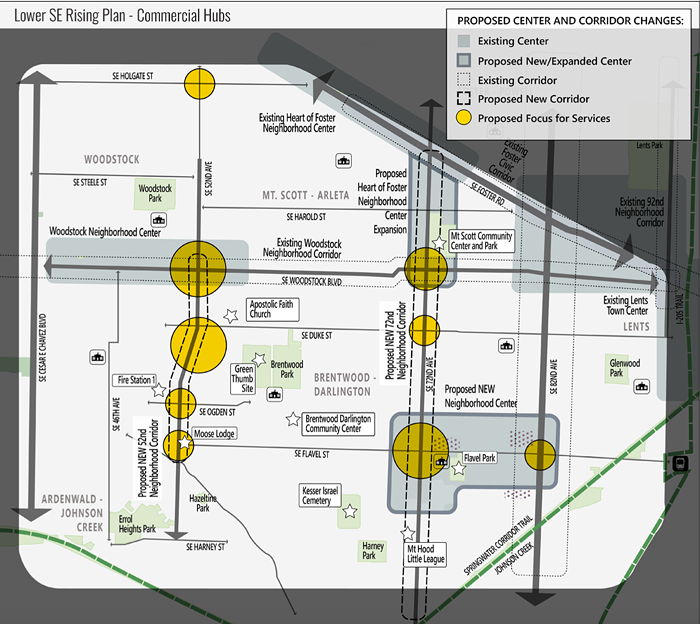

With the Lower Southeast Rising Area Plan, led by the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) and Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS), the city wants to course-correct. The plan, which primarily focuses on the Brentwood-Darlington neighborhood as well as parts of Woodstock, Mt. Scott-Arleta, and Lents, aims to reshape land use and transportation in areas of Portland. The goal is to provide opportunities for neighborhood businesses, create more multi-unit affordable housing complexes, and make it easier and safer for people to get around and access what they need.

After three years of planning, the Portland Planning Commission released a recommended draft for the Lower Southeast Rising plan earlier this month.

Throughout the planning period, area residents have provided mixed testimony about the project’s goals. While many people want to see improvements like sidewalk infill and other street safety measures, others are concerned about how the plan might push current residents out of the neighborhoods they’ve lived in for years. Project planners say they hope to address those concerns through efforts to maintain the current community, while ensuring the area is equipped to handle new residents and become more self-sustaining.

A hearing for the plan is set to go before Portland City Council later in April.

How yellow-lining dictated lower SE Portland’s fate

Lower Southeast Portland has a long history of disinvestment from the city, evident from the area’s lack of sidewalks, accessible bus lines, and tree canopy coverage. This can be partially attributed to the area’s historical classification as a “yellow-lined” part of the city.

Back in the 1930s, the New Deal-created Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) began appraising neighborhoods across the country for their lending risk, largely based on the racial and ethnic makeup of an area (in addition to economic demographics). The HOLC determined the majority of lower Southeast Portland was “definitely declining” and advised lenders to practice caution when providing home loans to people who wanted to buy houses in the area.

Home values in formerly “yellow-lined” neighborhoods still have some of the lowest overall values in the city, keeping housing prices relatively affordable, but also limiting residents’ access to important infrastructure.

Many neighborhoods in the Lower Southeast Rising project area are some of the oldest in the city, founded in the late 1800s and further populated during the early 20th century’s streetcar “golden age.” Some of these neighborhoods were then annexed into the city of Portland, but Errol Heights (now Brentwood-Darlington) remained unincorporated until 1986, when unchecked sewage problems in the community forced Portland’s government to step in. Brentwood-Darlington’s late annexation is another factor contributing to its relative disinvestment.

“In large part because of its history and development before it was part of the City of Portland, the Lower Southeast Plan Area lacks much of the same infrastructure and access to businesses and services that Portlanders in other parts of the city enjoy,” the plan’s latest draft states. “This has led to a quieter, rural-feeling pocket of the city cherished by some community members even as some find the lack of infrastructure and proximity to services a real hindrance to living the lives they want to.”

Proposed land use changes

City planners say the area was never built to handle the growth and transportation needs of modern day Portland.

Zoning code throughout the project area overwhelmingly prohibits commercial uses, leading to a lack of neighborhood grocery stores and restaurants within a short travel distance. According to project planners, “community members indicated their top land use priority for the area was the need for more local businesses and commercial opportunities.”

Only 10 percent of the project area is zoned for multi-unit dwellings, meaning rental housing supply is lower than in other parts of the city. Low-income housing complexes can be found in eastern portions of the plan area, particularly near the Lents Town Center, but are otherwise mostly absent.

The plan lays out proposed zoning code changes that will enable Brentwood-Darlington and the surrounding area to become “complete neighborhoods where residents can meet their needs locally.” One proposal is to create a new neighborhood center in the heart of Brentwood-Darlington around SE 72nd Avenue and Flavel Street, providing a new place for residents to fulfill their day-to-day needs within walking distance. The plan also proposes designating SE 52nd and SE 72nd Avenues as “neighborhood corridors,” allowing for expanded housing and commercial opportunities along the streets and at its key intersections.

New transit routes and infrastructure

With regard to transportation needs, many streets in the project area lack sidewalks entirely. In addition, the project area has a dearth of public transportation and bike routes, despite its compact street grid creating ideal conditions for traveling outside a car.

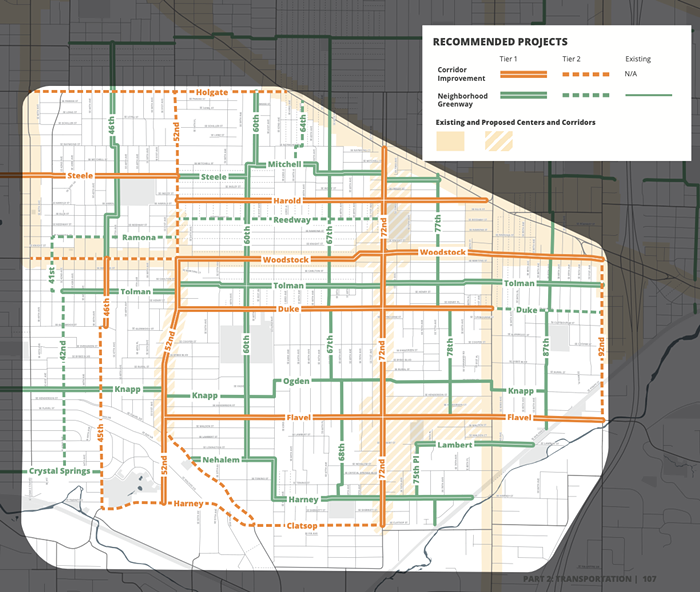

The recommended draft plan proposes to fix that, adding corridor improvements and neighborhood greenways that would support safe biking, walking, and access to transit.

The largest recommended corridor improvement project is a $9.7 million renovation of SE Woodstock Blvd from 52nd Avenue to Foster Road, adding enhanced pedestrian crossings, upgrading additional bike lanes to protected lanes, and more. The plan also proposes building new neighborhood greenways—which utilize speed humps and car traffic diverters to create low-stress transportation corridors for people biking, walking, or rolling—on SE 60th Ave from Mitchell to Nehalem, SE Tolman St from 52nd to 92nd, and SE Knapp St from 32nd to 52nd, among others.

City planners also want to expand residents’ access to transit. Right now, none of the TriMet bus routes that cross the Lower Southeast core area run on a frequent basis, making it longer and more difficult for residents to rely on TriMet for daily transportation needs. To fix this, the lan proposes switching Line 19-Woodstock/Glisan and Line 71-60th Avenue to frequent service, meaning the buses would come every 15 minutes. The plan also suggests a few route changes to help construct a “bus grid” in the area.

One other major infrastructure deficit in lower SE Portland is its lack of tree canopy, resulting in more intense heat events for people in the project area compared to other places in the city. One way PBOT wants to fix this is through a pilot project that will repurpose street parking to make room for trees. Construction on this project will begin this summer just east of Brentwood-Darlington on SE Duke Street between 82nd and 92nd Avenues.

Most of the infrastructure plans outlined in the recommended draft are currently unfunded. The report lays out several potential near-term and future funding sources like gas tax revenue, system development charges and the Quick Build Program, which funds small transportation safety projects but is insufficient for significant sidewalk infill or repaving plans.

Future, long-term sources of funding for the plan could include Metro Regional Flexible Funds, which distribute federal grants to local projects, the Metro Parks and Nature Bond, Local Improvement Districts, and public-private partnerships. Portland City Council’s approval of the plan will pave the way for BPS and PBOT to scout out project funding.

Community response is mixed

So far, the Lower SE Rising plan has been met with mixed reviews from the community. One particularly contentious topic is the proposal to increase housing density in the area, which is currently made up of predominantly single family housing.

One endorsement for increased housing density came from Erin Cottle Hunt, a professor at Reed College who recently moved to Portland.

“I would like to purchase a home here in Portland (eventually), but am largely priced out of the market,” Hunt wrote in public testimony last September. “Changing some of the zoning designations in the Southeast neighborhoods could allow more development which could help increase housing affordability.”

Others had a more critical response.

Jessica Murri, a first-time homeowner on SE 72nd in Brentwood-Darlington, said it was a “gut punch” to hear that her home’s property value may be affected by the plan.

“I see opportunity for multi-family apartments 10 blocks to the east, where SE 82nd is brimming with empty car lots and abandoned buildings,” Murri wrote. “It is a main thoroughfare, closer to public transit, bus lines, the MAX and the Springwater Corridor. But I would ask you to leave our neighborhood intact.”

Jeff Mital asked planners if the “only path to [traffic safety] improvement comes from building giant apartments,” saying he didn’t see the link between larger multi-unit dwellings and street safety improvements.

The Lower SE Rising plan lays out the importance of considering land use and transportation projects in tandem with one another, pointing out that dense housing near commercial services facilitates sustainable, safe transportation because people will be able to walk, bike, or take transit to reach the services they need, rather than needing to rely on a car.

But planners do want to keep existing residents in the neighborhood. A letter from the Planning Commission to City Council states that commissioners heard concerns that zone changes to allow more multi-dwelling housing “could destabilize the community and result in the loss of relatively affordable ownership housing.”

“From a broad policy perspective, a failure to expand housing opportunities leads to a constrained supply of housing, higher housing prices, and additional displacement,” the letter states, adding the proposed zoning changes to allow multi-unit dwellings are concentrated along transit corridors and in the proposed neighborhood center.

The plan also includes proposals to ensure current residents are able to stay and benefit from the area’s revitalization.

Some residents say they’ll welcome any change to their neighborhoods, which they feel have been long abandoned. Mike Palmer, another resident who weighed in with public testimony last fall, said he and his neighbors have been “promised many things in the past and have been hugely disappointed by the city.”

“We care about our neighbors and this neighborhood and need this development. We need this done for future generations that live here,” Palmer said. “We’re tired of being ignored or put off until later.”

The current public comment period for the Lower SE Rising recommended draft is open until April 25, when the City Council hearing is set.